Original author: Joel John

Original translation: TechFlow

The killer app for cryptocurrencies has already arrived in the form of stablecoins. In 2023, Visa’s transaction volume was close to $15 trillion, while the total volume of stablecoins was about $20.8 trillion. Since 2019, stablecoins have traded $221 trillion between wallets.

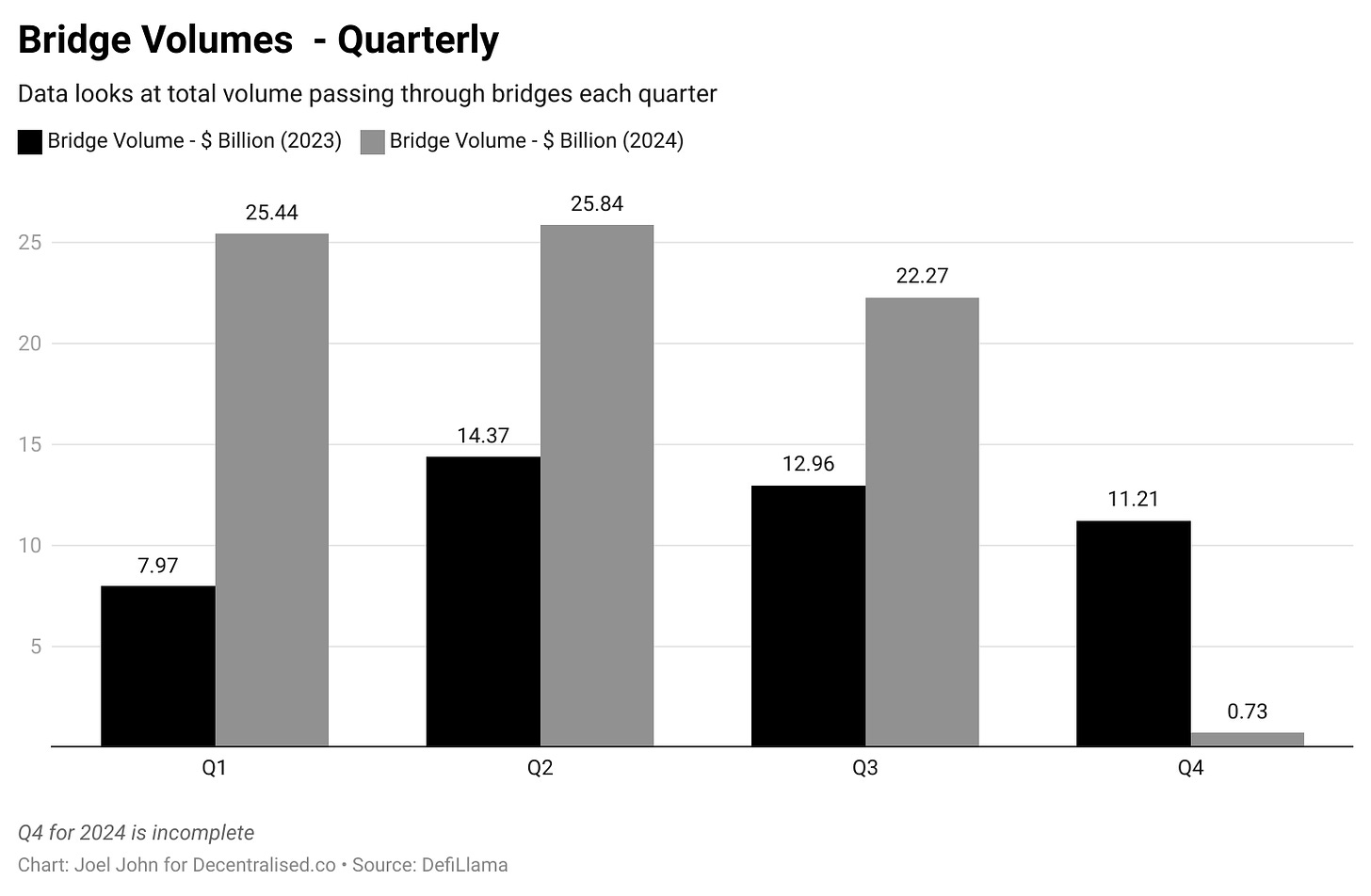

In the past few years, money equivalent to the global GDP has flowed through blockchains. Over time, this capital has accumulated on different networks. Users switch between different protocols in search of better financial opportunities or lower transfer costs. With the advent of chain abstraction , users may not even know they are using a cross-chain bridge.

Think of cross-chain bridges as routers for capital. When you visit any website on the internet, there is a complex network behind the scenes that ensures that the bits and bytes displayed are accurate. A key link in the network is the physical router in your home, which determines how the data packets are directed to help you get the data you need in the shortest possible time.

Cross-chain bridges play a similar role in today’s on-chain capital. When a user wants to transfer funds from one chain to another, the cross-chain bridge determines how the funds are routed so that the user gets the most value or the fastest speed.

Since 2022, Cross-Chain Bridge has processed nearly $22.27 billion in transactions. This is a far cry from the amount of money that moves on-chain in the form of stablecoins. However, Cross-Chain Bridge appears to earn more per user and per dollar locked than many other protocols.

Today’s discussion is about collaborative exploration of the business model behind the cross-chain bridge and the revenue it generates through cross-chain bridge transactions.

Show Revenue

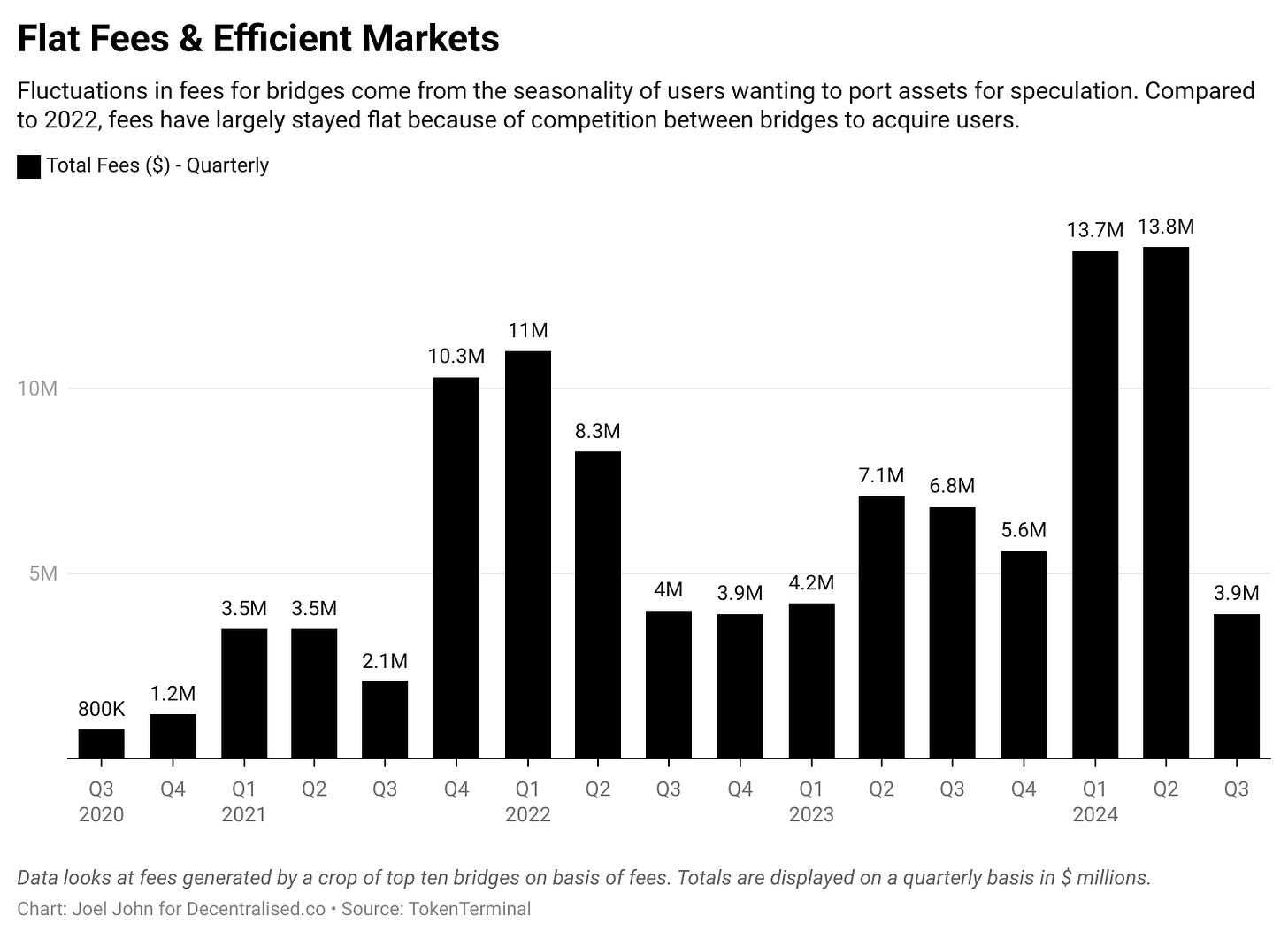

Since mid-2020, blockchain cross-chain bridges have generated nearly $104 million in fees. This number is seasonal as users flock to cross-chain bridges to use new applications or pursue economic opportunities. If there are no yields, meme tokens, or financial instruments available, cross-chain bridges will suffer as users will gravitate to the protocols they are most familiar with.

A rather sad (but funny) comparison is to contrast Cross-Bridge revenues with meme-coin platforms like PumpFun . Their fee revenues were $70 million, while Cross-Bridge generated $13.8 million in fee revenues.

The reason fees have remained flat even as transaction volume has risen is due to the ongoing price war between chains. To understand how they achieve this efficiency, it helps to understand how most cross-chain bridges work. One way to understand cross-chain bridges is to compare them to the hawala network of a century ago.

Blockchain cross-chain bridges are similar to hawala, connecting physically separated entities through cryptographic signatures.

While hawala is now widely associated with money laundering, a century ago it was an efficient way to move money. In the 1940s, for example, if you wanted to transfer $1,000 from Dubai to Bangalore — when the UAE was still using the Indian rupee — you had a few options.

You can choose to go through a bank, which can take days and require a lot of documentation, or you can go to a gold souk and find a dealer. The dealer will take your $1,000 and instruct a businessman in India to pay the corresponding amount to someone you trust in Bangalore. The money flows between India and Dubai, but it does not cross the border.

So how does this work? Hawala is a trust-based system, as merchants in the gold market and merchants in India often have long-standing trading relationships. Rather than transferring money directly, they may use a commodity (such as gold) to settle the balance later. Since these transactions rely on mutual trust between the participants, there needs to be a lot of confidence in the integrity and cooperation of the merchants on both sides.

How does this relate to cross-chain bridges? In many ways, cross-chain bridges operate in a similar way. For example, you might want to move funds from Ethereum to Solana in pursuit of yield, rather than from Bangalore to Dubai. Cross-chain bridges like LayerZero enable users to lend tokens on one chain and borrow them on another by passing user information.

Suppose that instead of locking up assets or giving out gold bars, these two traders give you a code that can be exchanged for capital at either location. This code is equivalent to a way of transmitting information. Cross-chain bridges like LayerZero use a technology called endpoints. These endpoints are smart contracts that exist on different chains. Smart contracts on Solana may not be able to directly understand transactions on Ethereum, and this is when oracles are needed. LayerZero uses Google Cloud as a validator for cross-chain transactions. Even at the forefront of Web3, we still rely on Web2 giants to help us build a better economic system.

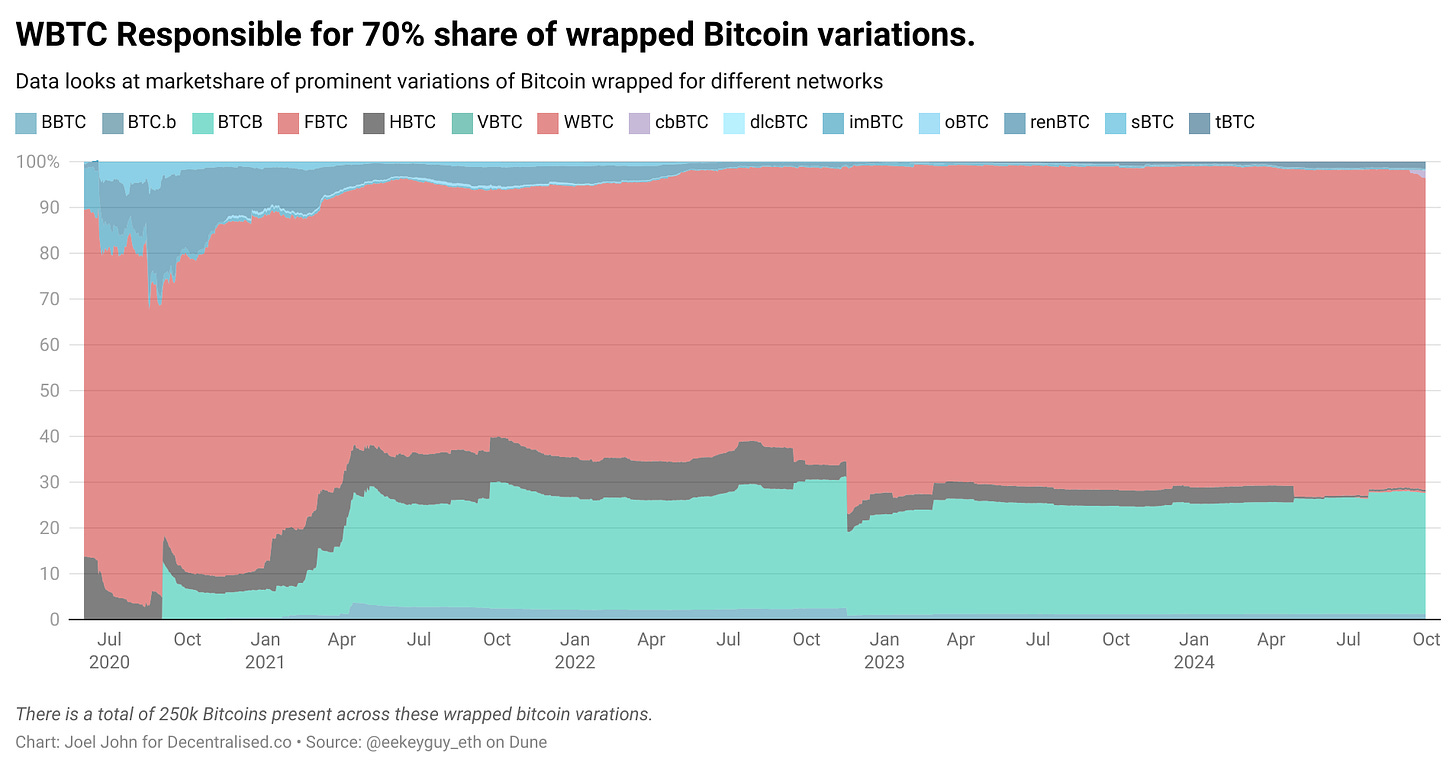

Imagine that the traders involved don’t trust their own ability to interpret the code. After all, not everyone has access to Google Cloud to verify transactions. Another way is to lock and mint assets. In such a model, if you use Wormhole, you lock your assets in a smart contract on Ethereum to get a wrapped asset on Solana. This is the equivalent of a hawala merchant giving you gold bars in India and you depositing dollars in the UAE. The asset is minted in India and handed over to you. As long as you return the gold bars, you can speculate with them in India and get your original capital back in Dubai. Wrapped assets on different chains are similar to gold bars - except that their value generally remains the same on both chains.

The chart below shows the various changes we have today to Bitcoin wrappers. Many of these were minted during the DeFi summer in order to create yield on Ethereum using Bitcoin.

The cross-chain bridge has several key profit points:

Total Value Locked (TVL) - When users deposit capital, those funds can be used to generate yield. Currently, most cross-chain bridges do not lend idle capital, but instead charge a small transaction fee when users transfer capital from one chain to another.

Relay fees — These are small fees charged by third parties (like Google Cloud in LayerZero) on every transfer. These fees are paid for validating transactions on multiple chains.

Liquidity Provider Fee - This is a fee paid to individuals who deposit capital into the cross-chain bridge smart contract. Lets say you are running a hawala network and someone is moving $100 million from one chain to another. As an individual, you may not have enough capital. Liquidity providers are individuals who pool their funds to help complete the transaction. In return, each liquidity provider takes a small portion of the fees generated.

Minting costs — Cross-chain bridges can charge small fees when minting assets. For example, WBTC charges 10 basis points per Bitcoin. Of these fees, the main expenses of the cross-chain bridge are to maintain forwarders and pay liquidity providers. It creates value in TVL through transaction fees and the way assets are minted on both ends of the transaction. Some cross-chain bridges also adopt an incentivized staking model. Suppose you need to make a $100 million hawala fund transfer to someone on the other side of the ocean, you may need some form of economic guarantee to ensure that the other party has sufficient funds.

He might call up his friends in Dubai and form a joint venture to prove that he can complete the transfer. In exchange, he might even return some of the fees. This operation is similar to staking in structure. Except that instead of using dollars, users come together to provide the networks native tokens in exchange for more tokens.

So how much revenue is generated from all this? What is the value of a dollar or a user in these products?

economics

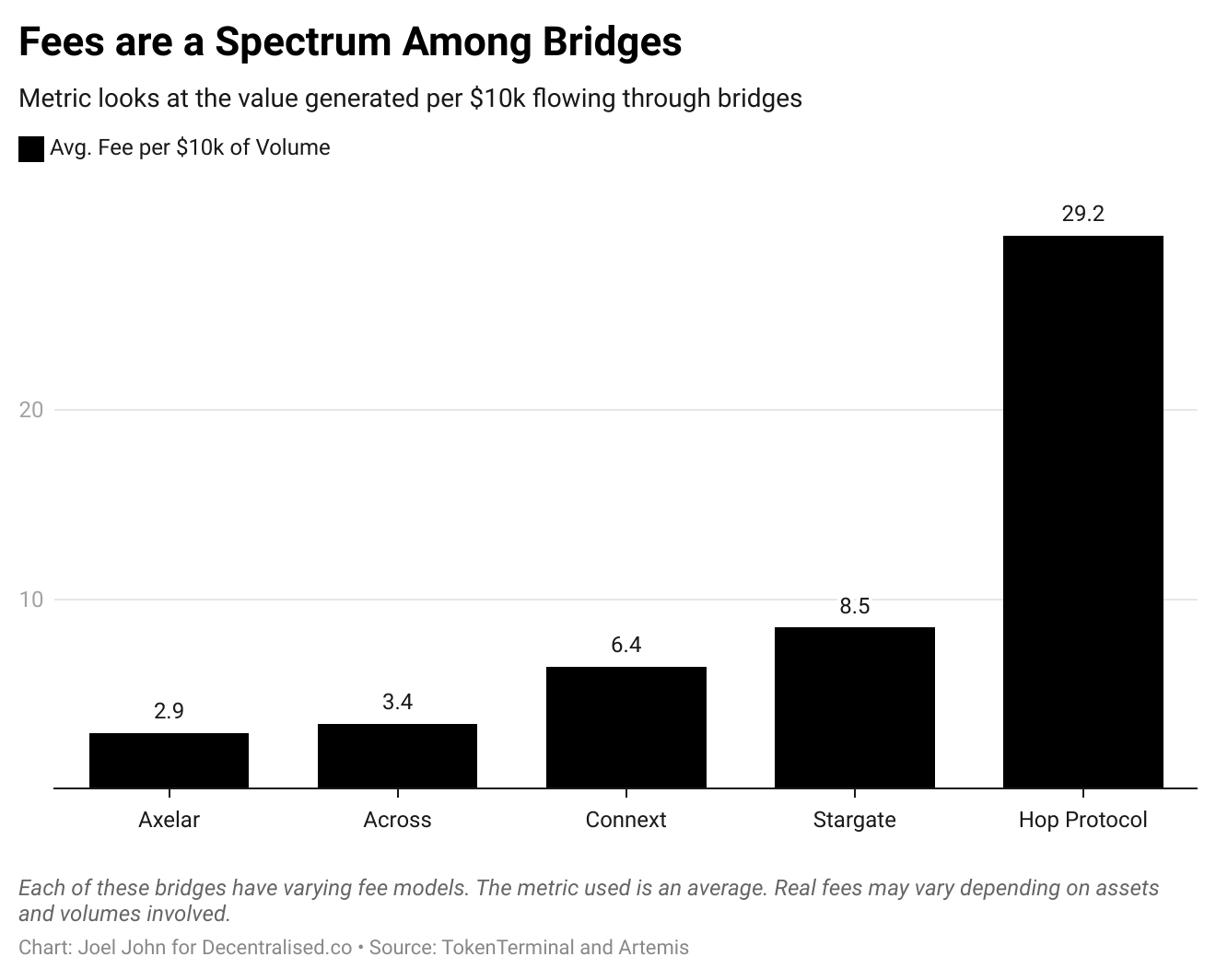

The following data may not be precise enough because not all fees go to the protocol. Sometimes the fees depend on the protocol used and the assets involved. If the cross-chain bridge is mainly used for long-tail assets with low liquidity, it may cause users to suffer slippage in transactions. Therefore, when looking at unit economics, I want to clarify that the following does not reflect which cross-chain bridge is better. What we care about is how much value is created throughout the supply chain during the cross-chain bridge event.

A good starting point is to look at the volume and fees generated by each protocol over a 90-day period. This data covers metrics through August 2024, so the numbers reflect the previous 90 days. We assume that Across has higher volume because of its lower fees.

This provides a rough idea of how much money is flowing through the cross-chain bridge in any given quarter, and the fees they incur during the same period. We can use this data to calculate the fees that the cross-chain bridge incurs for every dollar that passes through its system.

For ease of reading, I calculated the fees incurred to transfer $10,000 across these cross-chain bridges.

Before I begin, I want to clarify that this is not to say that Hop charges ten times more than Axelar. What it means is that for a $10,000 transfer, a cross-chain bridge like Hop can create $29.2 in value across the value chain (e.g. liquidity providers, forwarders, etc.). These metrics will be different because of the nature and type of transfers they support.

What’s interesting is when we compare the value captured on the protocol to the value of the cross-chain bridge.

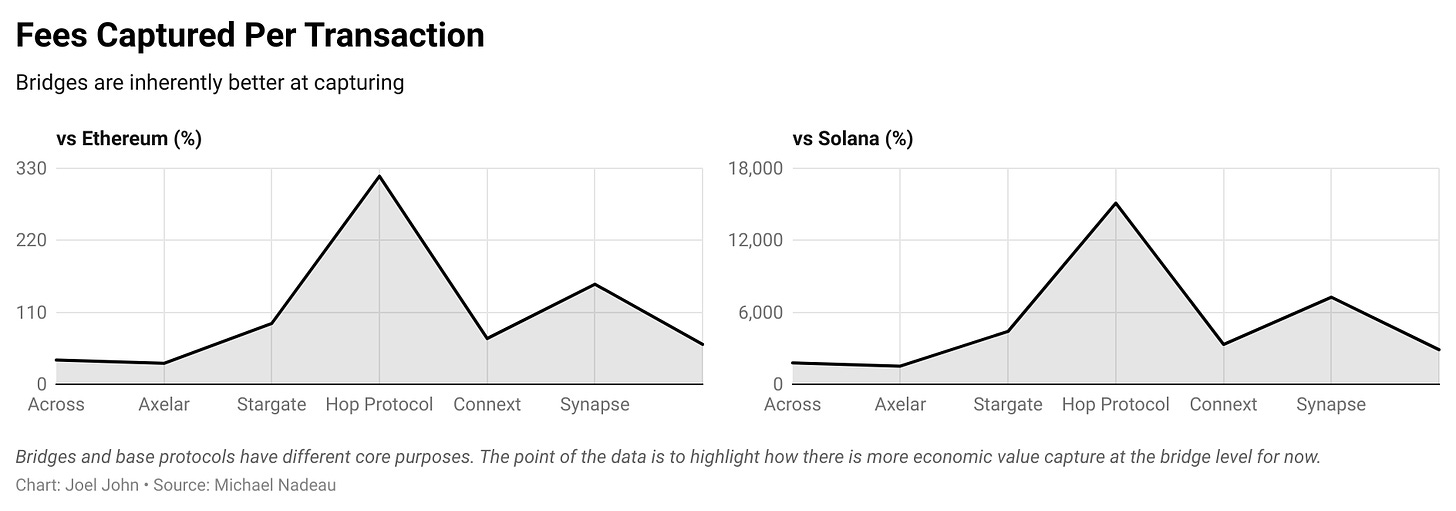

For benchmarking, we looked at the cost of transferring money on Ethereum. As of the time of writing, during a period of low gas fees, fees on ETH were approximately $0.0009179, while fees on Solana were $0.0000193. Comparing cross-chain bridges to L1s is somewhat similar to comparing a router to a computer. Storing a file on a computer will cost much less. But the question we are addressing is whether cross-chain bridges capture more value than L1s from an investment perspective.

From this perspective, combined with the above metrics, one way to compare the two is to look at the USD fees captured per transaction by individual cross-chain bridges and compare that to Ethereum and Solana.

The reason why several cross-chain bridges capture lower fees than Ethereum is because of the gas costs incurred when conducting cross-chain bridge transactions on Ethereum.

One could argue that Hop Protocol captures 120x more value than Solana. But that would be missing the point, as the fee models of the two networks are quite different. We are interested in the difference between economic value capture and valuation, as we will soon see.

Of the top seven cross-chain bridge protocols, five have lower fees than Ethereum L1. Axelar is the cheapest, at just 32% of Ethereum’s average fee over the past 90 days. Hop Protocol and Synapse currently have higher fees than Ethereum. Compared to Solana, we can see that L1 settlement fees on high-throughput chains are orders of magnitude cheaper than current cross-chain bridge protocols.

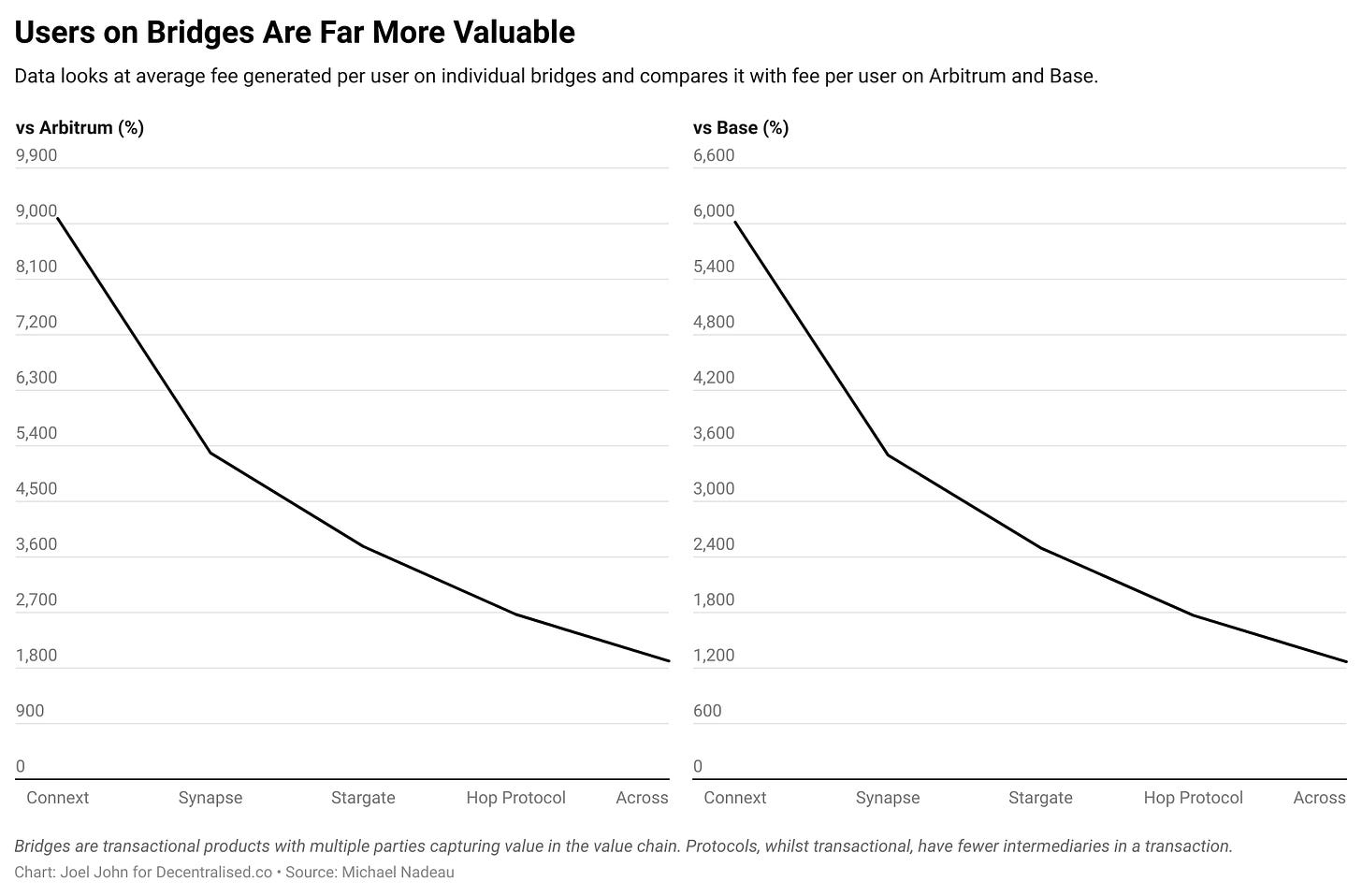

One way to further enhance this data is to compare the cost of transacting on L2 in the EVM ecosystem. For context, Solana’s fees are just 2% of regular fees on Ethereum. For this comparison, we’ll be choosing Arbitrum and Base. Since L2 is designed for extremely low fees, we’ll use a different metric to measure economic value — average daily fees per active user.

Over the 90 days we collected data for this article, Arbitrum averaged 581,000 users per day and generated an average of $82,000 in daily fees. Similarly, Base averaged 564,000 users per day and generated $120,000 in fees.

In contrast, cross-chain bridges have fewer users and fewer fees. The highest of these is Across, which has 4,400 users and generates $12,000 in fees. Therefore, we estimate that Across generates an average of $2.4 in fees per user per day. This metric can then be compared to the fees generated per active user of Arbitrum or Base to assess the economic value of each user.

The average user on the bridge is more valuable than the user on L2. The average Connext user creates 90x more value than the average Arbitrum user. This is a bit of an apples and oranges comparison, as the gas fees for cross-bridge transactions on Ethereum are quite high, but it highlights two clear factors.

Money routers like today’s cross-chain bridges may be one of the few product categories in cryptocurrency that can generate significant economic value.

As long as transaction fees remain prohibitively high, we may not see users moving to L1s like Ethereum or Bitcoin. Users may be introduced directly to L2s (like Base), and developers may choose to absorb the gas costs. Alternatively, there may be a situation where users simply switch between lower-cost networks.

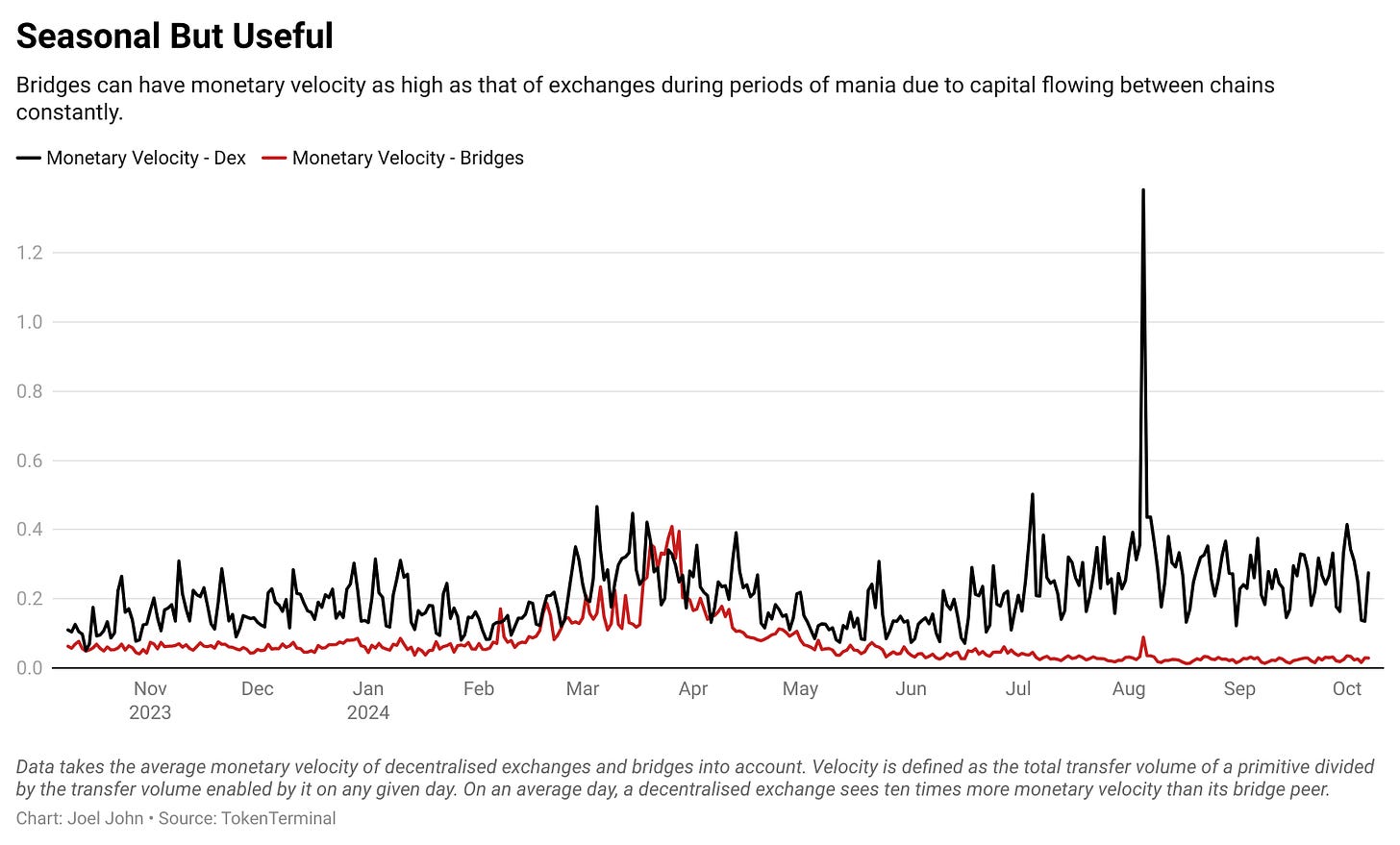

Another way to compare the economic value of cross-chain bridges is to contrast them with decentralized exchanges. The two are very similar in function, both of which enable the conversion of tokens. Exchanges allow conversion between assets, while cross-chain bridges convert tokens between blockchains.

The above data is only for decentralized exchanges on Ethereum.

I avoid comparing fees or revenues here, and instead focus on capital velocity. Capital velocity can be defined as the number of times capital moves between smart contracts on a cross-chain bridge or a decentralized exchange. To do this, I divide the amount of transfers on any given day by the cross-chain bridge and decentralized exchange by their TVL.

As expected, the velocity of currency on decentralized exchanges is much higher as users often swap assets multiple times a day.

Interestingly, however, when excluding large L2-oriented cross-chain bridges (such as Arbitrum or Opimism’s native cross-chain bridge), currency movement speed is not much different from decentralized exchanges.

Perhaps in the future we will have cross-chain bridges that limit the amount of capital they accept, and instead focus on maximizing yield by increasing the velocity of capital. That is, if a cross-chain bridge can move capital multiple times a day, and pass the fees on to a small fraction of users who park capital, it will be able to generate higher yields than other sources in cryptocurrency today.

Such a cross-chain bridge may have a more stable TVL than traditional cross-chain bridges, as expanding the amount of parked funds will result in reduced returns.

Is a cross-chain bridge a router?

Source: Wall Street Journal

If you think the VC rush to infrastructure is a new phenomenon, take a historical look with me. In the 2000s, when I was a kid, Silicon Valley was abuzz with enthusiasm for Cisco. Logically, if Internet traffic increased, routers would capture a ton of value. Just like NVIDIA today, Cisco was a high-priced stock because they built the physical infrastructure that supports the Internet.

The stock peaked at $80 on March 24, 2000, and as of this writing, is trading at $52. Unlike many dot-com bubble stocks, Cisco’s share price has never recovered. Writing this post in the context of the meme-coin craze got me thinking about the extent to which cross-chain bridges can capture value. They have network effects, but are likely to be a winner-take-all market. This market is increasingly moving toward an intent-and-solver model, with centralized market makers filling orders in the background.

Ultimately, most users don’t care about the level of decentralization of the cross-chain bridge they use, they only care about cost and speed.

In such a world, the cross-chain bridges that emerged in the early 2020s might be akin to physical routers, closer to being replaced by intent- or solver-based networks akin to 3G for the internet.

Cross-chain bridges have reached a mature stage, and we are seeing multiple approaches to solve the age-old problem of cross-chain asset transfers. One of the main drivers of change is chain abstraction , a mechanism for transferring assets across chains without the user realizing it. Shlok recently experienced this with Particle Network ’s Universal Account.

Another way to drive volume is through innovation in product distribution or positioning . Last night, while researching meme coins, I noticed how IntentX is using intent to integrate Binance’s perpetual markets into its decentralized exchange product. We are also seeing cross-chain bridges for specific chains evolve to make their products more competitive.

Whatever the approach - it is clear that cross-chain bridges, like decentralized exchanges, are hubs for large capital flows. As an infrastructure, they are here to stay and continue to evolve. We believe that domain-specific cross-chain bridges (like IntentX) or user-specific cross-chain bridges (like those enabled by chain abstraction) will be the main drivers of growth in this space.

Shlok added a point in discussing the article that routers in the past have never captured economic value by the amount of data transferred. Cisco makes about the same amount of money whether you download a terabyte or a gigabyte. In contrast, cross-chain bridges make money based on the number of transactions they facilitate. So, in all respects, they may have different fates.

At this point, it’s safe to say that the phenomenon we’re seeing with cross-chain bridges is similar to the development of the physical infrastructure for internet data routing.